Nothing seems more refreshing than a tall, frosty glass of water after a long day under the tropical sun. It’s sheer bliss if it’s blended with some spices and a bit of fizz.

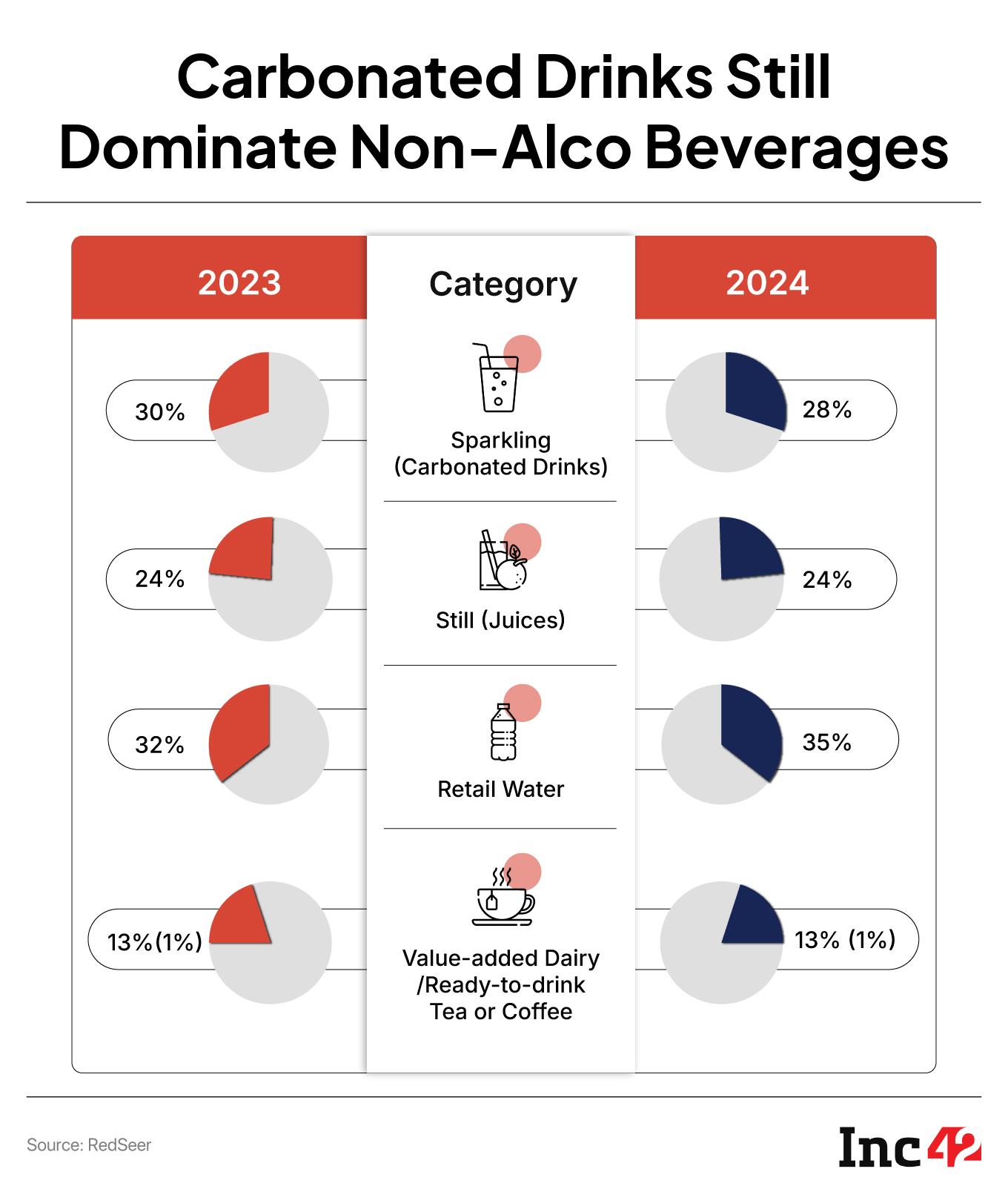

Amid continuing cola war around the globe and raging cry against carbonated drinks, ethnic Indian brews seeped in and soon went in vogue, disrupting India’s $32 Bn non-alcoholic beverages market. But, when three brothers from Punjab had set out in 2017 to create a demand for spiced drinks, the choices were few and the supplies fewer.

Lahori Zeera spiced up the ever-mutating ecosystem of age-old beverages with natural ingredients and the right amount of fizz that suited the evolving preference of the Indian youth.

“We saw ethnic Indian drinks were vastly underrated. They had never been positioned at par with western colas, and nothing was available on shelves in a hygienic, packaged form. That was the whole thesis when we moved in,” Nikhil Doda, one of the three founders, recounted the story of the making of Lahori Zeera.

As a whole-new segment opened up, a slew of homegrown brands began crowding up. Even cola majors zoomed in on the jeera jamboree. While Coca-Cola came up with RimZim, Indian conglomerates like Dabur and Tata too entered the fray as consumers fancied local flavours.

What’s intriguing in this backdrop is that the simmering turf will be a test for the Lahori playbook.

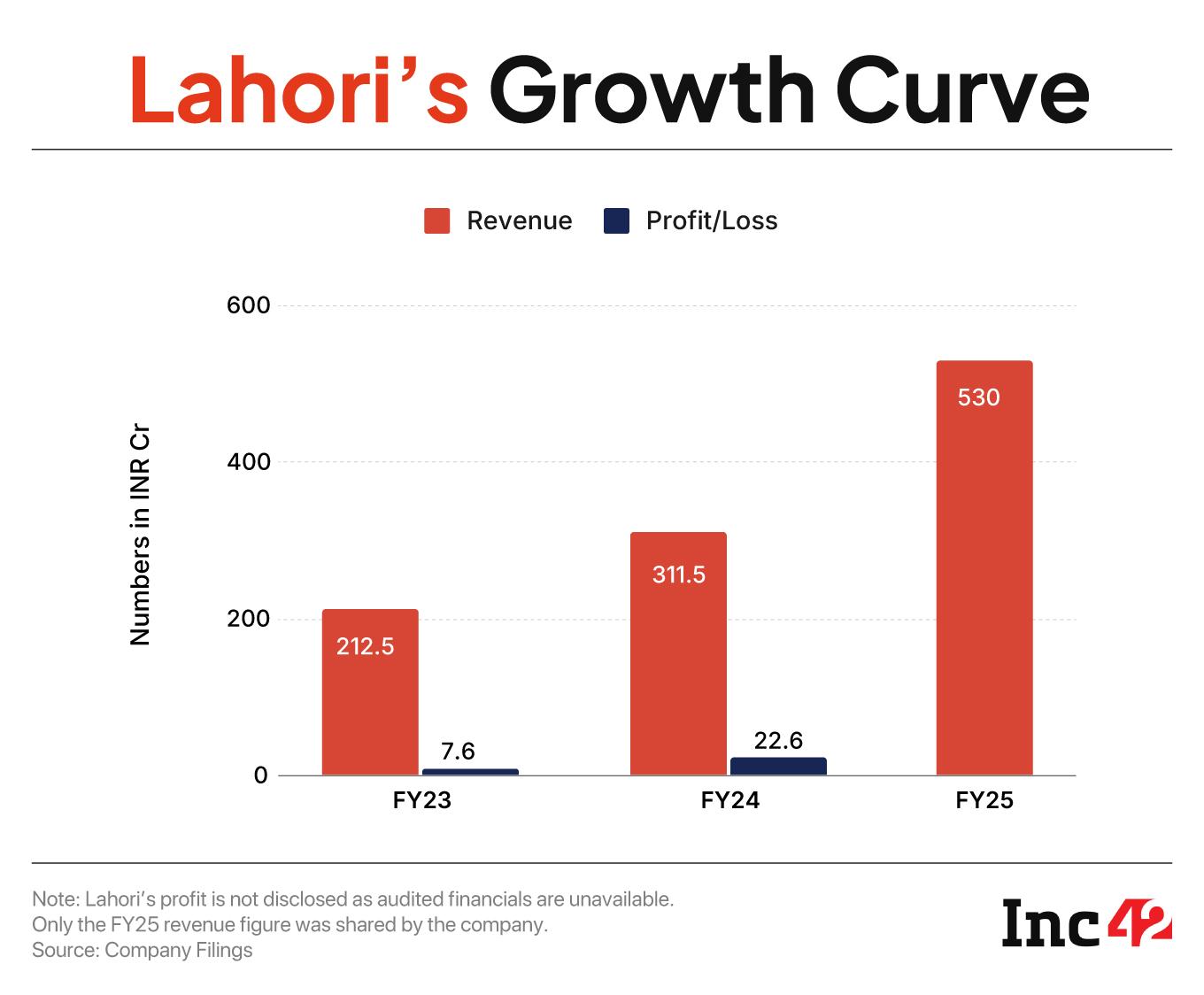

Back in 2020, Lahori did business of around INR 83 Cr. But the game changed after Covid. By FY23, its revenue shot past INR 212 Cr, as more and more people pivoted to healthier alternatives and ingredients like turmeric, ginger, tulsi, and jeera came up for their healing properties.

The brand scaled rapidly from there on, growing two-and-a-half times in the next two years to a revenue of INR 312 Cr in FY24 and closed FY25 with a topline of INR 530 Cr, claimed the founder. The company, however, stayed bootstrapped until it touched an annual recurring revenue of INR 150 Cr in 2020.

Going Reverse On Market RiddleTo put the distribution channel in place, the founders started work even before they rolled out the product. In the early days, they took their trial batches, made at home, to distributors simply to test the waters. The feedback was encouraging. “They said ‘it tastes good, it is sellable… You should give it a shot’,” Doda said.

Lahori Zeera took its name from an ethnic cumin-flavoured drink, popular in Northern India.

But, the enthusiasm hardly translated to commitment. The distributors refused to hand out any advance and, instead, offered to take the stock on credit, unsure if the product would actually move off the shelves.

The founders decided to take the reverse way. They convinced retailers in Chandigarh to take a small bet of INR 200, rather than asking them to risk several lakhs of rupees upfront. Within months, Lahori was available in 200 to 300 outlets, sales picked up, and repeat orders began pouring in. The buzz in a small city like Chandigarh made the product visible quickly. As retailers began reordering, the very same distributors who had hesitated earlier, took notice.

“That was our foot in the door with the right set of people – the same ones we wanted to work with from day one,” Doda said.

Lahori ensured that the distributors made healthy margins and built a strong local team to support them. Instead of spreading too thin, the company doubled down on depth to build its presence in markets like Chandigarh, Panchkula, Ludhiana and Ambala. Word spread through distributor networks, driving organic interest from neighbouring markets. A sustainable supply chain started building up.

Lahori’s inverse strategy of starting with retailers drove demand to win over distributors, and go deep into the core markets. The company now claims to be getting 200–300 distributor enquiries every day from across India.

Distribution was only one piece of the jigsaw. Lahori still had plenty of hurdles to cross. Beverage is a capital-hungry business that needs high capex for setting up plants, bottling lines, logistics, raw material sourcing, branding, and technology to stay efficient.

“We struggled to meet the demand from the second year itself, when we found our track. Whatever money we made, we ploughed it back into the business. We kept doing that for four to five years and simply grew with the profits we generated,” Doda said.

In December 2012, the founders received a call from an investment manager in Chandigarh, who had spotted their bottles on retail shelves. On inquiring, the shopkeepers had bluntly told him that “the drink sells, but the company can’t meet the demand”.

When the investment manager reached out to the founders, they admitted that money was a constraint. “There is demand, and we are growing. This is the pace we can grow at with the capital we have,” Doda recounted his response to him.

The investment manager connected Lahori to Belgium-based private equity firm Verlinvest, which had been eyeing India for years, but was yet to find a compelling story to back. After its top consultants studied the market and consumer behaviour, Verlinvest was convinced, and Lahori raised $15 Mn in funding against a minority stake.

The fund-raise marked a turning point for Lahori. From being a small founder-led hustle, the company moved on to be a more professionally managed business, reaching out to the Big Four auditors, forming a second line of management, and laying out formal processes. With external stakeholders, came discipline, structure, and validation.

Just before the funds were credited, an overnight hike in the GST rate on carbonated fruit drinks from 12% to 40% left the company shuddered. For a business that relied on natural ingredients like lemon juice, this was a massive blow.

How It Resolved The Plant ParadoxDemand determines the growth of a business – that’s the usual format. For Lahori, it’s been the other way round. It has always battled with growing demand and short supply. Reluctant to raise funds, the company failed to live up to the demand because of inadequate manufacturing facilities and capacity shortage.

As Lahori worked on the bottleneck, it spotted a solution in co-branding. Partnerships could help it expand the capacity without bearing the full capital burden. Lahori had started off with a modest plant near Chandigarh. Over the last four to five years, the facility expanded steadily, yet it remained far from enough.

A second unit came up in Gujarat after the first round of fund-raising. Located strategically close to Mumbai, it gave Lahori easy access to the markets in Western India. A third plant is set to go live in Lucknow within the next two months, according to the founder.

But as the company scaled, it realised that for a product so tightly tied to freshness and local demand, three or five plants alone wouldn’t help. “Beverages need proximity. That insight shaped our next leap to go for an asset-light co-bottling model,” Doda said.

The company has partnered with experienced bottlers to set up smaller plants every 300–400 km. Six such units have been roped in so far.

This summer, the company produced close to 5 Mn bottles daily across its two plants. With Lucknow and the six co-bottling units joining the network, Lahori expects to double that capacity by March, crossing 10 Mn bottles a day, according to the founder.

The estimates are in sync with the expansion strategy the company has thrashed out. This year, Lahori plans to enter the markets of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana that remained largely untapped. By next summer, it hopes to see its bottles on the shelves across these states.

International interest around the ethnic Indian beverages brand too is building up, Doda said. It has received interest from a few Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, where the flavour profiles resonate strongly with the local preference. While India remains the immediate focus, Lahori sees the UAE as its first foreign venture. Discussions with bottlers are underway and the brand expects to make its overseas foray in the next one to two years.

The company raised INR 200 Cr in primary funding from Motilal Oswal Wealth earlier this year. It helped sharpen the focus on expansion, especially in South India, where homegrown rival Megha Fruit Processing, which makes Bindu Jeera, has a strong foothold.

Lahori offers four to five flavours in its carbonated range, including Nimbu Shikanji, Kaccha Aam, and Masala Jeera, and the product sits at the “magical price point” of INR 10. “The strategy is rooted deeply into India’s FMCG story,” Doda said.

Think of Parle’s INR 5 biscuits or single-use shampoo sachets that drove mass adoption. The logic is simple: when a product is cheap enough to be an impulse purchase, it breaks through income barriers and penetrates both urban and rural markets seamlessly.

That approach stands in stark contrast to global giants like Coca-Cola and Pepsi. While both the companies have experimented with smaller SKUs for India, their entry-level packs usually start at INR 20, with larger bottles scaling up quickly to INR 40–90.

“The beverages market in India is massive, largely dominated by players with strong brand perception and deep marketing budgets. But our approach was different: focus on the price point and build something slightly differentiated,” Doda said.

Lahori aims to close FY26 with a topline of INR 800 Cr, but the way ahead is likely to get bumpier with increasing competition from multinational giants. The next few years will test how the Lahori playbook plays out in India’s booming ethnic beverages market.

[Edited by Kumar Chatterjee]

The post Can Lahori Keep Its Fizz As Global Giants Eye India’s Ethnic Beverages? appeared first on Inc42 Media.

You may also like

Jaishankar, Goyal meet US counterparts amid wrinkles in ties; no immediate resolution on trade issues

Wasted voyage: Afghan teen hides in plane's landing gear to reach Delhi; deported next day

BJP ally TMP, Congress, CPM slam govt for not being invited to PM Modi's event

M&S shoppers rush to buy 'comfy and smart' £60 leather boots

UK university with 'Halal certified menu' sparks huge debate